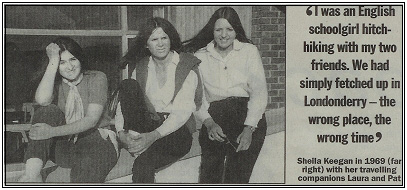

Sheila Keegan

The

July 4, 1999 issue of London’s The Sunday Telegraph newspaper

carried an excellent full page account of Sheila’s experience

when as a 16 year old student touring Ireland she got caught-up

in rioting in the Bogside during which she took a photograph of

children making petrol bombs which were being used in the

fracas. The article described that event and a trip back 30

years later during which she located and interviewed the

children in the photograph. Sheila is the daughter of Betty

Tinneny of Killahurk, Carrigallen.

The

July 4, 1999 issue of London’s The Sunday Telegraph newspaper

carried an excellent full page account of Sheila’s experience

when as a 16 year old student touring Ireland she got caught-up

in rioting in the Bogside during which she took a photograph of

children making petrol bombs which were being used in the

fracas. The article described that event and a trip back 30

years later during which she located and interviewed the

children in the photograph. Sheila is the daughter of Betty

Tinneny of Killahurk, Carrigallen.

***

It was August 12, 1969 and I stood in Rossville Street, in the

Bogside district of Londonderry, surrounded by a Catholic

crowd. Earlier in the day, the Apprentice Boys had marched

through the city, in their annual comoration of the Siege of

1688. Tension between Catholics and Protestants was palpable.

Trouble was expected.

It

started with jeers and stone throwing.Within hours, it had

escalated into fierce rioting between Catholics and the RUC.

The Battle of the Bogside had begun, marking the beginning of 30

years of violence.

It

started with jeers and stone throwing.Within hours, it had

escalated into fierce rioting between Catholics and the RUC.

The Battle of the Bogside had begun, marking the beginning of 30

years of violence.

I

stood, transfixed as a line of RUC officers 20 abreast, wielding

batons and riot shields, broke through makeshift barricades and

charged straight into us. A crowd of Loyalists taking advantage

of the breach, followed behind the catholic crowd scattered in

panic.

I

was not a rioter, I was an English schoolgirl hitchhiking around

Ireland in the summer holidays with my friends, Pat and Laura.

We each had Irish Catholic parents. They believed Ireland would

be a safe place for our first solo holidays. We had simply

fetched up in Londonderry – the wrong place, the wrong time.

Disbelief at facing a wall of charging policemen gave way to

panic. We turned and ran. We scaled a high wall and sought

sanctuary in nearby flats.

It was impossible to leave the Bogside that night. A Catholic

family, the Quiggs, kindly put us up and we left the next

morning.

I

knew little of Irish history at that time. My father talked of

being a runner for the IRA as a child. He told stories of the

Black and Tans cruising the countryside in drunken mobs,

randomly shooting at passers-by and burning down cottages –

along with their inhabitants. He described how in Belfast, pigs

heads were stuck on spikes with the label “Cured in Rome”.

I had laughed and

walked away. What had that to do with my life as a teenager in

London in the late 1960? I was listening to Pink Floyd in Hyde

Park. I was more interested in Vietnam than Ulster.

Suddenly and inadvertently, I had entered my fathers’ world.

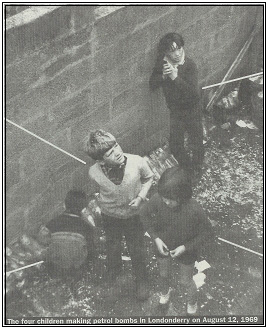

I

took six photos that day with my Kodak Instamatic: the

Apprentice Boys’ march, the Rossville Street crowd, four

children making petrol bombs.

I

did not visit Londonderry again for 30 years, not until I

returned last week to make a programme for Radio 4. I wanted to

find the people in the pictures, to see what had happened to

them in the intervening years, to find out how their lives had

parralled the Troubles. In particular I wanted to find the

children in the petrol bomb picture. Had they grown up to become

bank managers? IRA men? Would they want to be found?

With the help of the local newspaper, the Derry Journal, I

tracked down the family we had stayed with. Then I hit luck.

Sure, that’s one of the Kelly brothers, probably Tony,” said a

lady at the community centre after studying my photograph.

I

was sent to a taxi rank in a dark street to find Patty Kelly,

Tony’s brother. From there, I was directed to Paddy’s house. I

arrived unannounced asking for Tony. Paddy was wary, but

invited me in. I showed him the photograph.

“No, that’s not Tony,” he said. I felt deflated. Had I been

sent on a false trail? Later I discovered that Tony was an IRA

prisoner who had escaped from Long Kesh. He is still on the

run.

Paddy seized me up for an hour, while we talked about the peace

talks and my Dad. Then he picked up the photograph again.

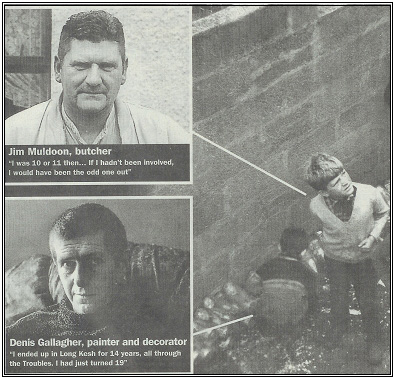

“That one there. I think that’s Jim Muldoon.”

He phoned Jim, he agreed to come round to Paddy’s after work.

Jim is a burly, humorous man, now working as a butcher. He was

delighted to see the photo of his earlier exploits.

“I was 10 or 11 then,” he said. “Those petrol bombs were

shipped down to William Street. Someone older would have put in

the petrol and the rags. We were on school break. It was to

pass the time. You were never doing it hurt anybody. If my Mom

had seen me she would have killed me. She thought I was a

saint.

“If I hadn’t been involved, I would have been the odd one out.

I use to get out of bed at night, put my mask on; you had to

follow the crowd. I thought I was the Lone Ranger; it was all a

game, but there were bullets sometimes.

“You did well to track me down. My wife can’t even find me some

weeks.”

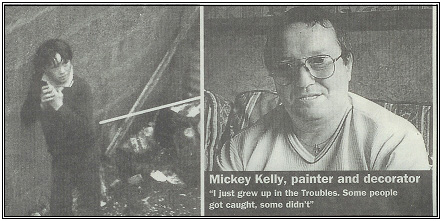

Jim pointed to the dark haired boy leaning against the wall.

“Hey, Paddy. Isn’t that your brother Mickey?”

It was. I was

taken to Mickey’s flat. Mickey, too was pleased to see me. He

was married and worked as a painter and decorator.

“There were some crazy times then,” he said, “We were only

wains. The police were trying to move in and the wains were

making petrol bombs and the big fellas would come up.

“There use to be a side gate and we’d take the petrol bombs and

put them in the boot of their car, and then we would go up and

down the barricades. It wasn’t too bad as long as you weren’t

smoking. It made us feel big then, helping. My Mom could smell

the petrol on my cloths, but she couldn’t do much.

“I just grew up in the Troubles same as everybody else. Some

people got caught. Some people didn’t get caught. At the very

top of the Rossville flats, the army had a post. There was a

fire door and a young fellow set a booby trap and the army came

and the booby trap went off.

“Bloody Sunday was the scariest time of the lot. I was in

William Street with two boys behind me and they shot the two

boys whom I was standing beside. They just dropped beside me.

One of the boys was killed. I was 14.

“It’s not as bad now as it was. My wife works in a factory.

Two of her friends are Protestant and we went to Blackpool last

year with them.”

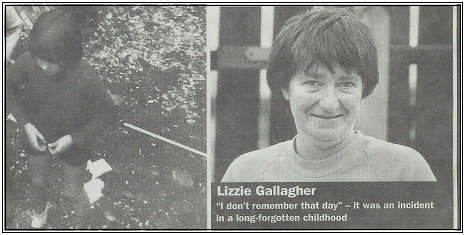

Mickey pointed to the other two children in the picture. “They

are Gallagher children. That’s Lizzie and Denis Gallagher.

Denis got life in jail. He’s out now,”

My next visit was to Mrs. Gallagher, the children’s mother. She

reared 12 children in a staunchly republican family and was

proud of her son Denis.

“I don’t regret one minute of what he was in. I don’t. He was

fighting for his country. That’s all that mattered to me.

There was not trouble with Denis at all. He was very good.”

“Mrs.Gallagher’s

daughter, Lizzie, was visiting her mother but she was quiet. ‘I

don’t remember,” she replied, when I asked her about August 12,

1969. For her it was another day in a long-forgotten childhood.

“Mrs.Gallagher’s

daughter, Lizzie, was visiting her mother but she was quiet. ‘I

don’t remember,” she replied, when I asked her about August 12,

1969. For her it was another day in a long-forgotten childhood.

The next day, however, I met Denis. He was a cautious man,

slightly wary of me, but welcoming and hospitable. He lives

with his wife and two small children. Like Mickey, he now works

as a painter and decorator.

He looked at the photograph wistfully. “At that times all the

wains were running around and helping as much as possible. I

remember the air being full of CS gas; we were always choking.

Later it became really serious. I ended up in Long Kesh for 14

years, all because of the Troubles.

“I had just turned 19. I was arrested and charged with

handling explosives and attempted murder. I got two life

sentences for it. I suppose today, looking back at that

photograph, that was my starting off on the way to prison.

“I never had regrets. I never ever believed that I was wrong.

It was just the way things worked out. Violence was part of

life. I always believed there will never be a solution until

there is total democracy in this country. I would like to see a

united Ireland: you can’t divide a country then tell people they

can have no say in it.

“Fourteen

years is a big chunk of anyone’s life, but hundreds went through

the same thing, on both sides. I would rather have had a normal

life, a life like anybody else: to have got a job, got married

before I did. I am nearly 40 years of age and my eldest child

is only six. I should have been going to my daughter’s wedding

now.

“Fourteen

years is a big chunk of anyone’s life, but hundreds went through

the same thing, on both sides. I would rather have had a normal

life, a life like anybody else: to have got a job, got married

before I did. I am nearly 40 years of age and my eldest child

is only six. I should have been going to my daughter’s wedding

now.

“But I’m glad the violence has stopped. If it’s not going to be

resolved in the near future, there is no point in people dying.

It is up to the people to implement the agreement or it will

spiral out of control again.”

When I left Londonderry in 1969, I was in a state of

considerable excitement after all that had happened. I was just

as excited when I left last week; my trip could not have been

more successful. Yet it was excitement tinged with deep

sadness; a sadness for all that has happened in Northern Ireland

in the 30 years since that first visit, and sadness that I had

not made time to listen to my father. It is too late now. He

died in 1986.

Article and photos courtesy of Sheila Keegan.